I was making my way to my seat near the back of the plane, when I had this flash of recognition followed shortly by a sinking feeling:

I'd lost my water bottle.

AAAAAHHHHH! I ever-so-briefly wondered: could I -- should I -- get off the plane to retrieve it? Wander through the waiting area in the Portland airport? And then I realized going back to get a water bottle was all kinds of wrong and I'd never see that lovely water bottle ever again.

What sort of water bottle, you might ask, would put thoughts of exiting a plane into my mind? They still serve water and drinks on planes (for now). Why the angst?

Well, it was a sweet little stainless steel water bottle featuring a logo from the conference and festival I'd just attended, XOXO. And besides how forgetting it made me feel like a dork -- what am I, an absent-minded preschooler? -- it was a tangible reminder of the very real community I'd just spent 3 days joining. Who wants to lose a feeling of belonging?

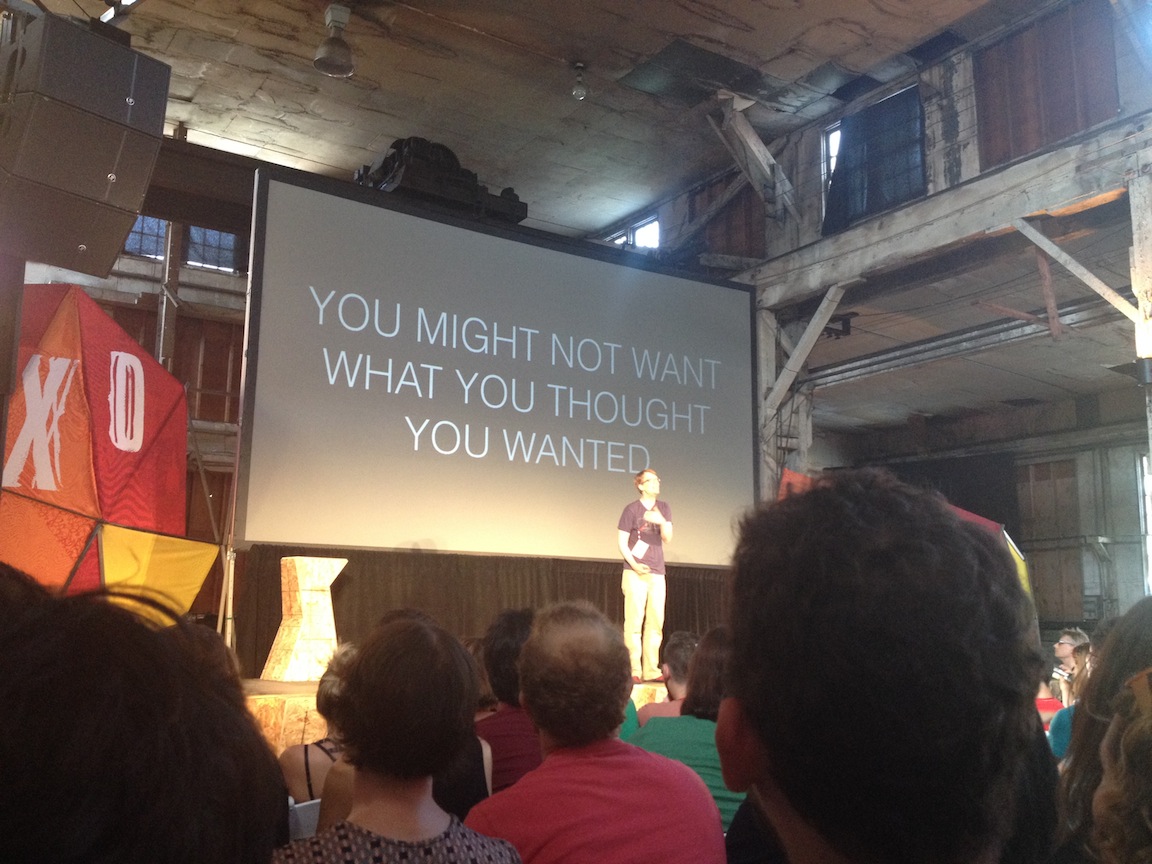

The Redd, a former factory converted into temporary tech conference hotel ballroom in Portland.

I'll choose to blame the Andys, I guess. That would be Andy Baio and Andy McMillan, the founders and organizers of the festival. It seems unfair, I know, to blame the people responsible for creating and giving me the water bottle for my loss of it, but it makes sense in some perverse way, right? If they hadn't created this festival and all the experiences within it, then I wouldn't be sad about losing this totem that could have been a daily reminder of those experiences.

The conference -- this year's edition was its third iteration -- is described as "an experimental festival celebrating independently-produced art and technology." What does that mean, though?

If you wanted to describe the conference as a tech conference, you could do so without drawing any snickers. There were many people from technology firms large and small in attendance. I talked to programmers (lots of programmers), data visualizers, designers. I'm sure that if I were part of that community in my daily life I could have -- and would have -- had more conversations that discussed APIs, whatever those are.

(I kid. I know what APIs are. Sort of.)

But I am not part of that community. My dad was many years ago -- maybe if I'd told my story about attending SIGGRAPH as a teenager with him more than 25 years ago I'd could've earned some IT cred -- but me? No. I have a middle-class job I enjoy very much but that is emphatically not in the art and/or technology fields. I was at XOXO because I:

a) won a lottery (well, multiple lotteries, more on that later),

b) write and talk about kids music for fun and, occasionally, (comparatively little) money, and

c) knew enough about the Andys and their previous conferences.

I thought it'd be a fun time and that I might learn something.

So for me, XOXO was not a tech conference. It wasn't even a creatives conference.

It was, above all, a conference modeling possible ways to negotiate life.

My game of Marrying Mr. Darcy -- so, so fun.

We joke in my day job that if you learn something new -- on your own, not from someone else in the office -- you get to take the rest of the day off. Doesn't matter how job-related the fact is or isn't -- in fact, the less related to the job, the better the joke when somebody tells us some incredible fact they just learned and then says, "OK, I'm outta here, see you tomorrow." Although we joke about it (no, we don't actually leave the office), there's something serious underlying that conceit. It's the idea that curiosity is a valuable trait, sometimes for its usefulness to the job at hand and sometimes for its (current) uselessness to the job at hand.

I suspect many XOXO attendees would subscribe to that notion. I met puppeteers, house concert organizers, people who develop apps and websites or played in bands on the side. I met very few people with narrow interests. Collectively and individually, there was a pronounced tendency towards interest in, if not outright enthusiasm for, new things. In this regard, I was amongst my people. I met lots of people, too -- it was a very outgoing crowd, or at least one in which wandering up to a conversation in progress or talking with someone waiting for lunch from the food carts parked outside the conference building was expected.

I'm a believer that conferences are remembered not by the ostensible purpose of the conference -- the talks, the workshops -- but rather the entertainment and conversations surrounding the conference. XOXO scored very highly in that regard, attracting a group of interested (and interesting) people and then giving them spaces in which to interact when the talks were over. I was most acutely drawn to those events which allowed the highest degree of interaction -- Music (singing along and dancing with others is fun!) and especially the Tabletop event. I highly recommend Marrying Mr. Darcy, which I purchased on the spot after playing, and can also recommend the forthcoming Monikers. I danced and sang along to Pomplamoose with fellow XOXO attendee Lori Henriques one night, and John Roderick and Sean Nelson the next (Roderick playing a gig with a broken finger on his strumming hand for goodness' sakes). I played video games -- I almost never play video games.

Hey, it's Pomplamoose! (Live at Holocene, Friday night) Do not miss them, people!

I watched as the XOXO CEOs -- that is, Chief Enthusiasm Officers -- Andy and Andy sang and danced along with the rest of us. Yes, they had to deal with the major and minor annoyances involved in putting together such a large undertaking, but they also had figured out a way to structure their life for the weekend such that they could also take time to sing along, to indulge their joy in the carnival they'd brought to life.

Hank Green is a funny, funny man. Right!

Most of the talks during the daytime conference were good, with my attention only drifting through a couple of them. They will eventually be posted online, and I encourage you to check them out, particularly those from Erin McKean, Hank Green, Joseph Fink, Rachel Binx, Darius Kazemi, and Pablo Garcia and Golan Levin.

The talks themselves (16 in all) blur together a bit -- but you can search the #xoxofest tag on Twitter and find lots of pithy quotations from the presentation, half of them probably from Wordnik (now Reverb) founder Erin McKean. She talked about creativity, coining the phrase "an enthusiasm of Andys," and about how being creative in a separate field with no stakes (in her case, her affinity for sewing clothes for herself) offers her freedom.

She also talked about difficult times, how "The only way out is through." This is a slight reworking of Robert Frost's famous line from his 1914 poem "A Servant to Servants" -- "The best way out is always through," but the meaning is the same -- you can't escape difficult times, you just have to work through them.

I would offer a corollary piece of advice appropriate for XOXO that the only way in is, well, in. To start. That's probably an easy statement to make in the midst of hundreds of people who start and make stuff, but harder to hold onto a month later when you're at home with far fewer of those people around you. We are all interdependent, as several speakers reminded us, and so gratefulness is always a good approach, but those interdependencies and webs of support can be hidden too.

Hank Green of Vlogbrothers fame gave a talk notable for its movement (was he pacing? It sure felt like he was pacing) and for not taking much credit for his success. He essentially found it random (as did Joseph Fink, co-creator of the out-of-nowhere podcast-now-live-show phenomenom Welcome to Night Vale). And if success at some level is essentially random, then you need to think repeatedly about why you're doing something so you can adjust course if necessary. "Better to think about why you want something than what you want," Green said, and depending on the path your life takes, "you might not want what you thought you wanted." In other words (mine, to be clear): do something for how it makes you feel or because it's the right thing to do, not for the end result. Because you can't guarantee that end result.

I think that's Oregon peaches with toasted walnuts on top, some sort of chocolate with a hint of sea salt on the bottom.

I'm a straight, white male, reasonably fit and healthy, and with a middle to perhaps upper-middle class upbringing here in the United States. That means I've already been luckier than 95% -- 98%? -- of anyone who's ever lived in terms of the ease of my life.

It is the equivalent of having someone hand you two scoops of ice cream served in a waffle cone from Salt & Straw for no reason whatsoever. (I took one of my dinner breaks to walk there from the conference and eat ice cream. For dinner. It was worth it.)

It is the equivalent of winning the lottery. Maybe not the million-dollar jackpot -- though I suspect that over a lifetime those personal characteristics may very well have given me a million dollars worth of advantages -- but certainly a big deal.

And being at XOXO was like winning the lottery again. I literally won a lottery to attend -- that was how the Andys chose to divy out most of their passes to the event to people who applied online, and my name was randomly selected. It wasn't cheap, either -- $500 for the conference and festival pass, plus travel expenses. That middle-class day job I have? That allows me, with diligent budgeting, to sometimes do something like this.

So I spent a lot of time listening and thinking about privilege. For me, some of the most useful presentations and conversations of the weekend were the ones like that from Rachel Binx, who has founded a couple different companies, but who was brutally honest in recounting the times when running those business has been difficult financially. I talked with art dealer Jen Bekman about a presentation she found frustrating in a way I might not otherwise have understood. I got to see one of the iOS apps that the App Camp For Girls developed this past summer and talk about the need for more such environments with founder Jean MacDonald. I'd like to think I understood those concepts intellectually in my younger dats, but as a parent of a STEAM-obsessed Miss Mary Mack who's now thinking about high schools and math and programming, it's become more real for me. (All this, plus a talk about misogyny in gaming by Anita Sarkeesian, whose presentation was far more calm and rational than I would be if I'd had death threats lodged against me and my mere presence to give a talk required the presence of a bodyguard.)

The most subversive talk of the conference was from Darius Kazemi. I don't want to ruin his talk too much, but suffice it to say it was funny and served as a commentary on many talks at tech conferences and, to be honest, lots of conferences generally. Kazemi points out that a lot of people's success is based on luck -- he pinned the percentage of stuff that succeeds with the public at maybe 10%. This is similar to what musician Jonathan Mann said in a separate talk, and also echoed the comments of Hank Green and Joseph Fink. Both success and failure can be inexplicable.

Not that successful people don't work hard -- many of them do. Heck, I've won those lotteries I've mentioned above, and I still work hard. But to interpret your own success as based solely on work is to deny the power of randomness. Lots of people work hard and never achieve stunning success. Better, then, to focus on the process than the result and try as many things as you have time to. (David Lowery would agree.)

My XOXO was one of a billion possible XOXOs I could have had. Most of them would probably have been equally strange and wonderful. A handful might have unalterably changed my life (presumably for the good, but one never knows). But it's the XOXO I did have, and I'm grateful for it. (Thanks, Andy and Andy. You guys rock.) Being humble in the face of good fortune you know you're at best only partially responsible for is a good approach for life generally.

I won once more at XOXO, which I can barely believe. (Actually, I won at least once more beyond that, earning a free game for a score on a Shrek pinball game at a party Friday afternoon, something that I don't think I'd ever earned on any arcade game, pinball or electronic, but never mind that.)

I was one of six people picked to receive a NeoLucida, a small "camera lucida" drawing tool which refracts light so that the viewer can essentially trace an object sitting in front of him or her. The two men, Pablo Garcia and Golan Levin, who co-founded the company also gave a presentation, and their talk was notable for their pointing out that even in this high-tech society, the manufacture of things still requires people. The NeoLucida is put together by hand in China by people making far less per day than I make (see again, lottery).

I wanted the NeoLucida because I've never been comfortable with my drawing skills. That's another way of saying I'm really bad at it. But by serving as a drawing aid, the NeoLucida offers the opportunity to practice, while producing something that looks, sort of, like real life. (In particular, I'm looking forward to drawing members of my family.) I don't need for it to be perfect, I don't even need it to be good. I just want another way to express creativity, another process to learn, another way in.

In the end, that's what I'm choosing to take from XOXO instead of the water bottle. The water bottle is a physical reminder of something I did. The NeoLucida and the attitude of XOXO's attendees are reminders of something I'm doing now and what I should do in the future. As long as I walk through life with curiosity, humility, gratefulness, and awareness of others, I can be proud of the life I'm living.

Last week Jeff Bogle from the fine kids music website

Last week Jeff Bogle from the fine kids music website